Growing up in Taiwan as the son of a Chinese woman and a white American man, I did not fit into either culture. I suppose I weathered a deep, lifelong identity crisis. I found myself torn between two cultures, a guest in both but at home in neither one. At school, an English-speaking school for missionary kids, I found myself in a Western culture. At home, I lived in an American culture as communicated by my father, but one that was placed in a Taiwan context.

My father always accepted me. Having retired from the U.S. Air Force, my father spent a lot of time at home and was always there for me. He told me many stories and taught me many lessons; he remains the man I hope to one day become. I suppose he was the only one to understand, perhaps subconsciously, that his son was a Chinese-American amalgamation. Sure, I was more American than not, but I wouldn’t fit in in the United States, either. I did not discover that until I arrived at LAX in 1992; the first thing I saw was a billboard for an “adult bookstore” – talk about culture shock!

My mother has always had great hopes for me, hopes that she encouraged me to follow. She took my father to Taiwan in 1976, where they have remained for the last 30 years. Mom worked hard outside the home; I suppose she has a type-A personality. She used to come home and cook a meal, give me an allowance when she could, and then she’d be off again. She started many businesses, usually in the service industry, such as cafés or restaurants, but she never knew when to sell and get out. In the 15 years I grew up in Taiwan, my family was in or close to bankruptcy four times. We were, therefore, alternately well off or poor. I was always loved, and I never felt insecure, even that period of time when my family lived off egg sandwiches and donated clothing.

Both of my parents expected great things of me. They both wanted me to have more opportunities, better education, and a better life. I fully intend (even now) to provide for my parents in their old age in response to their love. I was expected to achieve, to excel, to succeed at all I set my heart upon; very often, that was indeed the case. After all, my family’s honor was at stake, and I couldn’t let my family down.

But, I am my father’s son. My mother expected me to be much more Chinese than I am. Sure, when I arrived in California I thought I was as un-American as you could get; I was wrong. My identity crisis merely came to the surface as I finally came to realize my fears were well grounded; I didn’t belong in Taiwan’s culture, and I didn’t belong here, either.

I spent 15 years of my life expecting to go the States and fit in, to finally be “home.” I expected to get an education and a job, find a wife and settle down. I didn’t think too much about kids, but I assumed I would have some (we won’t be having any). I always thought my parents would move here by the time I was 30 to 35 and live with my family.

What a shock to discover that I was not a natural fit in America! I feel comfortable now, but the first couple of years were a real struggle. Cathy, my loving wife, has been a great help in my journey.

It is due to all this that I feel deeply saddened by the distance that has come between my mother and me. It is not merely geography, but also emotions and culture. You see, I am not the son my mother thought I would be, that she hoped I would be. She also expected grandchildren that I won’t be able to provide. I had finally and completely failed my mother and let my family down.

My mother is convinced that I do not love her, and I cannot convince her otherwise. I am not her son (as far as she can tell), because I do not respond to her the way her son should respond to her. Instead, I have discovered that I am more my father’s son, for better or for worse.

I think the problem is actually cultural. This came as a realization after seeing a clip from

The Joy Luck Club. I heard my mother’s words in the thoughts of Lindo Jong, and I heard my own thoughts uttered on screen. Seeing the onscreen mother and daughter struggling to understand each other reminded me of my mother and me.

At one point in the movie, the mother (Lindo Jong) thinks to herself:

I could see her face looking at me... but not seeing me. She was ashamed... so ashamed to be my daughter.

Shortly thereafter, her daughter (Waverly Jong) says:

You don’t know, you don’t know the power you have over me. One word from you, one look, and I’m four years old again, crying myself to sleep, because nothing I do can ever, ever please you.

There is another scene from the movie that sounds familiar to me. One of the daughters says to her mother:

Well, it hurts, because every time you hoped for something I couldn’t deliver, it hurt. It hurt me, Mommy. And no matter what you hope for, I’ll never be more than what I am. And you never see that, what I really am.

My mother and I have had similar “conversations.” It is, in fact, a cultural gap, a generational gap common to immigrant families.

Unfortunately, my family does not fit the typical immigration family model. My mother is not a first-generation immigrant; she married an American and went back to live in Taiwan. I am not a second-generation immigrant; I was born here, raised among Americans overseas, then moved back to the U.S.A.

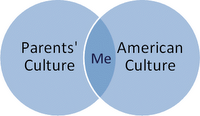

Yet, as a child, I did compartmentalize my different lives, between American school and Taiwan friends and home. I neither pursued Chinese culture nor rejected it; I took it for granted and only absorbed it in part. I readily accepted my American heritage, but did not know that I was not thoroughly American. As an adult living here alone, I had to integrate my different cultural compartments. Finally, I am comfortable being who I am.

However, now I see I do not know my own mother. My mother is hurt that I do not respond to her the way a Chinese son would. I absorbed some of her values, for example, I accept the mandate to provide for my parents in their golden years. It is likely that I would make a good American son, but I do not know how to express the respect and love I feel for her in her cultural forms, the way a Chinese son would love her.

My mother thinks I am ashamed of her, that I do not love her. That could not be further from the truth.

I do not understand my mother. When she hurts me with her words and actions, perhaps unintentionally but sometimes deliberately, I believe she is attempting to communicate the deep pain she feels. My mother may be hoping that I, seeing her pain, would respond appropriately, the way a Chinese son would.

In the end, I do not know how to be a Chinese son. My best hope to connect with my mother lies in communicating these very things to my father, and pray that he can communicate them to my mother. In the mean time, I struggle with how to honor my parents during this time. Perhaps, with some understanding, we can learn new ways of relating as mother and son.